Rio de Janeiro is a city of striking contrasts. From its world-renowned Carnival to its colonial history, the vibrant energy and timeless charm of Rio envelop visitors, leaving indelible memories. We experienced Rio during two distinct periods in 2018—our first visit coincided with the exhilarating frenzy of Carnival in February, while our second, quieter visit in November, allowed us to explore Rio’s colonial heritage, beaches, and cultural offerings. Together, these two visits painted a picture of Rio as a city where history, modernity, and diverse cultures collide, creating an experience that is unique and unforgettable.

Geography & Climate

Nestled between the forest-clad mountains and the Atlantic Ocean, Rio de Janeiro boasts one of the world’s most spectacular natural settings. The city sprawls along the shores of Guanabara Bay (Baía de Guanabara), which is dotted with over 130 islands, while Sugarloaf Mountain (Pão de Açúcar) and Corcovado—home to the towering Christ the Redeemer (Cristo Redentor)—dominate the skyline. Rio’s beaches—Copacabana, Ipanema, and Leblon—are world-famous for their beauty and vitality.

Rio’s climate is tropical, characterised by a hot, humid summer from December to March and a cooler, drier winter from June to August. During our February visit, temperatures soared, perfect for Carnival, while the November trip fell in the shoulder season, when the weather was slightly cooler but still pleasant, though Rio’s infamous rains made their dramatic appearances. Landslides and flooding, while not unexpected in this mountainous city, are ongoing challenges Rio faces.

History & Economy

Rio de Janeiro’s rich history stretches back to its founding in 1565 by the Portuguese, who named it São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro. The city grew from a small colonial outpost into a vital port, exporting goods like sugar and gold to Europe. Its pivotal role in Brazil’s development took a turn when the Portuguese royal family fled Napoleon’s armies in 1808 and relocated to Rio, briefly making the city the capital of the Portuguese Empire. This transformative period led to the construction of grand palaces, theatres, and public buildings.

After Brazil’s independence in 1822, Rio became the capital of the new republic and remained so until 1960, when the capital was moved to Brasília. Today, Rio’s economy is a blend of tourism, services, and industry, buoyed by its status as a major cultural hub. The city has hosted significant international events, including the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics, which helped reinvigorate its global image.

However, behind the glamour of Copacabana’s beachfront hotels lies a city grappling with economic disparity. Rio’s famed favelas, informal settlements that cling to the hillsides, are home to many of the city’s working-class residents, a stark contrast to the wealthier districts below.

Population & Diversity

As Brazil’s second-largest city, Rio is home to approximately 6.7 million people, with over 13 million in its metropolitan area. The city’s diverse population reflects its colonial past, with a significant portion of the population being of Afro-Brazilian descent, owing to Brazil’s long history of slavery. Alongside them, descendants of European, Indigenous, and Asian immigrants contribute to the cultural mosaic that defines Rio.

This diversity is most evident during Carnival when Afro-Brazilian cultural traditions, particularly samba, take centre stage. The social divide in the city is also visible in its geography: while the affluent Zona Sul neighbourhoods of Copacabana and Ipanema dominate Rio’s tourist image, the favelas provide a counter-narrative, rich with culture and community spirit despite economic hardships.

Beaches of Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro is renowned for its stunning beaches, each offering a unique atmosphere and experience. Copacabana, one of the most famous beaches globally, is located along the Atlantic Ocean and is known for its vibrant promenade lined with lively bars, restaurants, and the iconic black-and-white wave pattern along its walkways. Just a short distance away, Ipanema, also facing the Atlantic, captures the essence of Rio’s glamour, famously celebrated in the song “The Girl from Ipanema,” where visitors enjoy the lively beach scene, trendy beach clubs, and stunning views of the Pedra do Arpoador. Leblon, adjacent to Ipanema and also on the Atlantic, caters to a more affluent crowd, featuring upscale shops and quieter sands, perfect for families and those seeking a more relaxed beach experience.

In contrast, Flamengo and Botafogo beaches are situated along Guanabara Bay. Flamengo boasts spacious parks and beautiful views of Sugarloaf Mountain, providing a more tranquil setting for relaxation and picnics. Botafogo offers a picturesque backdrop with its iconic bay views, making it a favourite spot for locals to unwind and enjoy the sunset. Together, these beaches create a diverse coastal tapestry, reflecting the lively spirit and natural beauty of Rio de Janeiro, with Copacabana, Ipanema, and Leblon facing the Atlantic Ocean, while Flamengo and Botafogo are embraced by the bay.

Carnival 2018: Whirlwind of Colour, Controversy, and Culture (February 2018)

Arrival and Preparations

After a quick budget flight from Florianópolis, we arrived in Rio de Janeiro for Carnival 2018. Familiar with the city from the World Cup in 2014, we booked the same Copacabana hotel, Copacabana Suites by Atlantic Hotels. The weather in February was hotter than during our previous visits in winter, perfect for a beachside beer and a relaxed re-familiarisation with the area.

Our second day focused on logistics—picking up our Carnival tickets from the new office location in Copacabana. The energy of the young volunteers at the office was reminiscent of the sunny positivity seen during the World Cup, with their Carnival T-shirts and excitement for the event.

The evening was spent at Carretão Ipanema, enjoying an authentic Brazilian churrascaria. Alongside the array of meats, I even found brussels sprouts amongst the vegetables, which was a surprise. A walk along Ipanema Beach wouldn’t be complete without playing “The Girl from Ipanema” on the iPhone—its magic still lingers after more than 50 years. Despite fewer bossa nova sounds in the bars than expected, and the statue of Antônio Carlos Jobim on the beach, nevertheless the rhythms of Rio in the air set the tone for the days ahead.

City Tour: Bucket List Highlights – Corcovado, Pão de Açúcar, the Maracanã etc.

Our city tour the following day began early. Maria, our multilingual guide, skilfully managed a group of mostly South American tourists, corralling us through a day of breathtaking sights, lively conversations, and shared laughs between Argentinians and Brazilians about their respective football teams.

We ascended Corcovado early to avoid the worst of the crowds, though even by 9:30 a.m., the monument was packed. Standing under the towering Christ the Redeemer statue, one of the New Seven Wonders of the World, the sweeping view over Rio felt almost sacred. There’s a small chapel hidden at the monument’s base—a quiet spot amidst the masses. The monument itself, with its clean lines, reflects the 1930s Art Deco style, designed by French sculptor Paul Landowski and Brazilian engineer Heitor da Silva Costa. The iconic figure stands as a symbol of both faith and unity, overlooking a city bursting with contradictions.

After a whirlwind stop at the Maracanã Stadium, where both the 1950 and 2014 World Cup finals took place (with the famous upset of Brazil by Uruguay in the 1950 Maracanazo), we had some playful banter with the Argentinians. Brazil’s hopes for the 2018 World Cup in Russia seemed high, and the Argentinians didn’t miss a chance to rib the Brazilians about Germany’s 2014 victory.

The afternoon took us to Pão de Açúcar (Sugarloaf Mountain). The cable car ride, called “Bondinho”, felt like a scene from a Bond film—literally. The fight between James Bond and Jaws in Moonraker played out here, and I couldn’t help but feel the cinematic connection as we ascended the iconic peak. The views were less crowded than Corcovado but just as stunning, with Guanabara Bay, Niterói, and the sweeping beaches of Rio sparkling under a sunny sky. The Portuguese named the mountain after conical blocks of clay used to transport sugar in the 16th century—a reminder of Rio’s rich maritime history.

The day ended with a stop at the Catedral Metropolitana de São Sebastião, a bold modernist structure that evokes the pre-Columbian pyramids. Its towering, tepee-like form houses four enormous vertical stained-glass windows in vivid colours. Inside, the play of light and shadow was serene, a striking contrast to the bustling streets outside. Though largely a Catholic country, even here the group seemed more eager to move on—probably because lunch was next!

Carnival Parades: A Spectacle of Samba and Social Commentary

We attended two nights of the official samba parades at the Sambadrome, opting for Block 9 seating, the designated area for foreign visitors. In hindsight, the non-designated seats might have been just as good and much cheaper. The Sambadrome itself, built by Oscar Niemeyer in 1983, is a purpose-built 700-metre parade ground—a quintessentially Brazilian invention for Carnival.

Each school presented a parade of dazzling floats, feathers, and choreography, many incorporating deep social and political themes. The commentary on contemporary Brazilian society was at the forefront, with subtle (and not-so-subtle) digs at corrupt politicians and societal divisions.

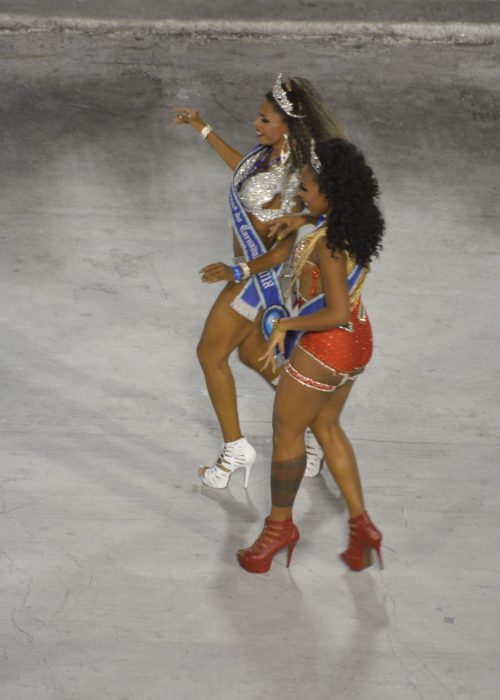

The top 13 Samba Schools, a sort of “Premier League” of samba, competed over two nights. Each school has a theme, complemented with original music that they structure their parade around. While to complete beginners to the process like us, it’s difficult to fully understand. However, what we could work out is that each parade starts with a small group that highlight the theme of the parade with some intricate moves and some awesome choreography. A pair of flag dancers that show off the school’s colours follows this. The main parade then consists of around seven large floats separated out by normally four or five large groups of parades with costumes that symbolise the themes. In between each group and the next float is usually a girl with massive feathers showing off her samba moves. In the middle of the parade there is group of musicians followed by a van with the name of the Samba School. Often each parade will have Brazilian celebrities in one of their later floats. The crowd’s reaction to seeing the celebrity is the clue for us novices when they appear.

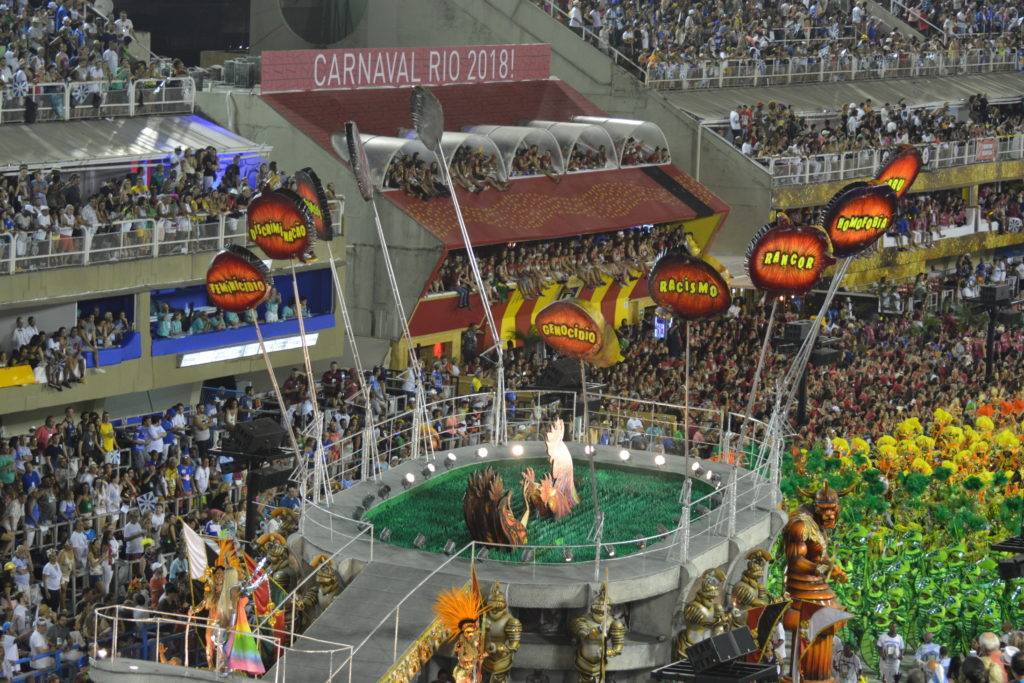

Beija-Flor, the final school to parade, stood out with its theme of prejudice. The floats depicted a range of issues, from homophobia to racism. A massive Frankenstein head split apart, revealing words like “Racismo” and “Genocido”, while another float showcased a favela beneath luxury condominiums. Celebrities, including the transgender pop star Pabllo Vittar, joined in, their presence adding a layer of contemporary relevance.

Equally memorable was the parade by Paraíso do Tuiutí, whose theme of slavery—both historical and modern—was visually powerful. Their portrayal of Brazilian President Michel Temer as a vampire drew gasps from the crowd. The school made history by featuring a British samba queen, adding an international dimension to the event. Other floats included one with modern condominiums next to a favela with a jail underneath the condominium, and one with a gunman taking a classroom of school children hostage.

Throughout the parades, references to death were strikingly frequent. Skulls, coffins, bones, and even devils appeared on many of the floats—perhaps reflecting deeper cultural attitudes towards mortality and the spiritual world.

The music is all constructed around the samba beat and is original each year. The Portela School had a song that sounded pretty much like the Italian Volare song from the 1950s and commonly adapted on the football terraces.

The spectacle, with its layers of cultural, political, and historical commentary, felt fresh and relevant. The entire city seemed to pulse with energy, from the massive floats to the samba rhythms that echoed long into the night.

Exploring Lapa and Santa Teresa

The Tuesday after Carnival was spent exploring the artistic neighbourhoods of Lapa and Santa Teresa. In Lapa, the arches were crowded with young revellers, still carrying the party spirit long after the official parades. Street performers and vendors mingled with the crowd, adding to the area’s chaotic charm.

Santa Teresa, by contrast, offered a more bohemian atmosphere. Set on a hill with stunning views over Guanabara Bay, the neighbourhood’s colonial architecture and quirky vibe attracted a cross-generational crowd. The area is known for its vibrant street art, and the Escadaria Selarón was packed with both locals and tourists taking in the colourful mosaic steps.

One notable change since our last visit in 2014 was the street art on the tram. Back then, the tram featured images of Brazilian footballers, but now it has shifted to more contemporary figures, reflecting the evolving cultural and political landscape of Brazil.

Carnival Hangover

By Wednesday, Rio felt like it was recovering from a city-wide hangover. The banks and shops had reopened, but the festive energy had shifted. On the beaches of Copacabana and Ipanema, which were much quieter, the music had changed too. The reggaeton of the weekend was replaced by the melancholic bossa nova, fitting for the slower pace and lingering exhaustion.

The Carnival’s results were announced, with Beija-Flor deservedly winning for its thought-provoking performance on prejudice. Paraíso do Tuiutí, with its slavery-themed parade, came a close second.

Our last day in Rio ended with a dramatic electric storm that flooded parts of the city and caused damage around the lagoon. But perhaps it was a fitting finale—washing away the remnants of the week-long party, leaving behind a city ready to face the post-Carnival calm.

Return to Rio: Colonial Echoes (November 2018)

Later in 2018, we returned to Rio de Janeiro after an extensive Dragoman overland journey from Boa Vista through the Guianas and Northern Brazil via Belém, Salvador, Ouro Preto and Brasilia. This time, Rio felt much quieter and more relaxed—a contrast to the frenzy of Carnival in February. November, being the shoulder season, meant fewer tourists and less crowded beaches. Weekdays were especially calm, giving us ample opportunity to relax on Copacabana and Ipanema beaches, where we watched the buses at day’s end ferrying locals back home with their beach gear in tow.

On Sundays, Avenida Atlântica was closed to traffic, transforming into a pedestrian paradise. Cyclists and joggers filled the broad avenue as the calm sea stretched out alongside them. Though Rio’s weather can be unpredictable in November, the storms we encountered were no different from the dramatic rains we saw back in February—when Rio rains, it rains hard.

Downtown Rio

Thursday was set aside for a more historical exploration of downtown Rio. The colonial architecture reminded us of Rio’s past as Brazil’s capital.

Igreja de São Francisco da Penitência

One of the most ornate and historically significant churches in Rio de Janeiro, showcasing the wealth and power of the Catholic Church during Brazil’s colonial period. Construction began in 1657, and it was completed in 1773, blending both Baroque and Rococo styles. The church is part of a larger Franciscan convent complex, situated near the Convento de Santo Antônio on a hill in downtown Rio. Its sister churches across South America, especially in Salvador, shared the same opulence, but the Carmelite church offered a quieter, almost regal atmosphere with its expansive cloisters.

The true splendour of the church lies inside. The entire interior is covered in rich wooden carvings, heavily adorned with gold leaf. It’s a textbook example of Brazil’s unique take on Baroque architecture, where exuberant decoration symbolised divine glory and the wealth of colonial Brazil. The chapel’s intricate detailing and ceiling paintings, particularly those by the Portuguese artist Manuel de Brito, create an overwhelming sense of opulence and spiritual grandeur.

São Francisco da Penitência is often considered one of the most stunning Baroque churches in Brazil, rivalling similar churches in Salvador and Ouro Preto. The overwhelming use of gold leaf—applied over intricate woodwork—was a hallmark of 17th- and 18th-century Portuguese religious architecture in Brazil, reflecting the country’s wealth from sugar and gold exports during that era.

Igreja de Nossa Senhora do Carmo da Antiga Sé, or the Old Cathedral of Rio de Janeiro

Another gem in the city’s historical centre. This church holds a special place in Brazilian history as it was the seat of the archdiocese of Rio and served as the royal chapel when the Portuguese royal family relocated to Brazil in 1808. It continued in this role until the current Metropolitan Cathedral was completed in 1976.

Originally a Carmelite convent founded in the 16th century, the current structure was built between 1761 and 1770, showcasing a restrained Rococo style, although less ostentatious compared to the nearby São Francisco da Penitência. The church became a symbol of imperial Brazil when it hosted key events in the royal family’s life, such as the coronation of Emperor Dom Pedro I in 1822 and his marriage to Maria Leopoldina of Austria.

Despite its more modest use of gold compared to other churches, the Carmelite Church stands out for its grandeur, scale, and historical significance. The church’s chapels and cloisters give a sense of the Carmelite order’s influence during Rio’s colonial period.

Theatro Municipal do Rio de Janeiro

One of Brazil’s most important cultural landmarks, is an opulent theatre that embodies the grandeur of Brazil’s Belle Époque. The theatre was inaugurated in 1909, at a time when Rio de Janeiro was modernising and seeking to position itself as a cultural capital in Latin America. Its design was inspired by the Paris Opera House (the Palais Garnier), a symbol of French culture and prestige, reflecting Brazil’s aspirations for progress and elegance.

The exterior of the theatre is adorned with columns, gilded details, and a grand copper dome, while the interior is no less impressive. Inside, marble staircases, stained glass windows, and grand chandeliers provide a luxurious setting for the performing arts. Brazilian artists and craftsmen, such as Eliseu Visconti, contributed to the rich decor, with Visconti’s murals decorating the theatre’s ceiling and foyer.

The Theatro Municipal was built during a period of economic prosperity, when Brazil was benefiting from its booming agricultural exports, particularly coffee. This wealth allowed for significant urban development projects, including the remodelling of Rio’s city centre. The theatre’s opulence was meant to symbolise Brazil’s entrance into the modern age, aligning the country with European cultural and artistic trends.

Today, the Theatro Municipal is the premier venue for opera, ballet, and classical music in Brazil, and its historical importance is matched by its continued role as a cultural hub in Rio de Janeiro.

Paço Imperial (Imperial Palace)

Located along Praça XV de Novembro, was once the heart of the Portuguese colonial administration in Brazil. It was originally constructed between 1738 and 1743 as the residence of the Portuguese viceroys who governed Brazil from Rio. When the Portuguese royal family fled Napoleon’s invasion of Portugal in 1808, the palace became the official residence of King João VI and later of Emperor Dom Pedro I.

The palace’s architectural style is relatively simple and functional, reflecting its origins as a colonial administrative building, but it gained historical significance through its role in Brazil’s transition from colony to empire. This was where Dom Pedro I declared Brazil’s independence from Portugal in 1822 with his famous cry of “Independência ou Morte!”(“Independence or Death!”). The palace was also the setting for numerous imperial and republican events until it ceased to function as a seat of government.

Today, the Paço Imperial is a cultural centre, with exhibitions and performances that reflect Rio’s rich history. The nearby waterfront, once a busy commercial port, has been revitalised in recent years with pedestrian walkways, public spaces, and art installations that enhance the area’s colonial heritage.

Catedral Metropolitana de São Sebastião

Commonly referred to as the Metropolitan Cathedral, is one of the city’s most iconic modern architectural landmarks. Its unique conical shape, reminiscent of a Mayan pyramid, sets it apart from more traditional churches in Rio and across Brazil. The cathedral was built between 1964 and 1979, designed by modernist architect Edgar de Oliveira da Fonseca. Its distinct design and massive scale reflect the influence of Brutalist architecture, which emphasises raw concrete forms and functionalist principles.

The cathedral’s design is meant to evoke the spiritual and communal aspects of sacred spaces, drawing inspiration from indigenous Latin American pyramids while breaking from European colonial church styles. Its external structure is a massive concrete cone, standing 75 metres (246 feet) tall, with a diameter of 106 metres (348 feet) at the base. The building’s massive scale can accommodate up to 20,000 standing worshippers or 5,000 seated, making it one of the largest cathedrals in Latin America.

The absence of traditional stained-glass windows along the sides of the building is compensated by four large vertical stained-glass panels that stretch from the ground up to the apex of the cone.

The Catedral Metropolitana is also notable for its juxtaposition against Rio’s colonial past, especially given its proximity to the historic downtown churches and government buildings. The modernist design symbolises Rio’s future-facing ambitions, standing as a dramatic contrast to the city’s historical architecture.

Pão de Açúcar

On Friday, we revisited Pão de Açúcar, choosing this spot over Corcovado. The crowds were far thinner than during Carnival, allowing us to truly appreciate the panoramic views of old Rio, Copacabana, and Niterói in the distance. From Flamengo Beach, where locals still swam despite the pollution, to the quieter Botafogo Beach, the juxtaposition of Rio’s natural beauty and its urban challenges was stark. But the calm atop Pão de Açúcar on that quiet Friday afternoon allowed us to reflect on Rio’s eternal charm.

To cap off the visit, we encountered the elephant parade, an artistic installation spread across the city with vibrantly painted elephants drawing attention to the plight of real-life elephants while showcasing the work of local artists.

Final Thoughts

Rio de Janeiro’s vibrant culture, breathtaking landscapes, and lively atmosphere make it a destination unlike any other. From the iconic beaches of Copacabana and Ipanema, where the Atlantic Ocean meets sun-kissed sands, to the stunning views of Sugarloaf Mountain and the Christ the Redeemer statue, every moment spent in this city is unforgettable. This contrast between the immense wealth embodied in historic landmarks such as the Igreja de São Francisco da Penitência, with its opulent baroque architecture and quantities of gold with the vibrant, grassroots spirit of Carnival is striking. During Carnival, samba schools take to the streets, celebrating not only the rich cultural heritage of Brazil but also addressing pressing social issues like inequality, racism, and environmental concerns through powerful performances and striking costumes. Carnival serves as a poignant reminder of the disparities within Brazilian society, juxtaposing the grandeur of Rio’s historic buildings with the voices of those advocating for change. This exhilarating experience, combined with the warmth of the Carioca people and the city’s rich history, leaves an indelible mark on all who visit. Whether you’re indulging in a delicious feijoada, exploring the artistic streets of Santa Teresa, or simply relaxing on a beach, Rio de Janeiro offers a unique blend of experiences that beckon travellers from around the globe.

The Rio de Janeiro Carnival has always been one of those must see events. We were not quite sure what to expect, having seen bit on TV and heard a few stories from friends who had been before, however nothing can quite describe before hand what it is like. Essentially the whole City feels like its been turned into a festival site and there are literally impromptu parties cropping up everywhere.

Dates: 07/02/2018 to 15/02/2018 and 22/11/2018 to 26/11/2018